Although I write about many topics on this blog (Shakespeare, science fiction, rock music, Tolkien), as much as possible I focus on eschatology and messianism–mainly Muslim, since my doctoral studies and several subsequent books dealt with that topic.

But Islam’s Mahdi/Twelfth Imam is not the only apocalyptic game in town. Non-Western (and Islam is a Western religion, coming out of Judaism and Christianity, with a little help from Zoroastrianism) cultures have their own brands of beliefs in a supernatural deliverer. My friend Dr. Richard Landes covers some of these in his brilliant work Heaven on Earth. The Varieties of the Millennial Experience (Oxford, 2011). However, I just discovered that Chinese history is rife with examples of such, as well. Matthew Dentice breaks down many of them in a series of “Patheos” posts, such as this one: “Other Themes in Chinese Eschatology.” I had some knowledge of Buddhism’s messianic Maitreya(s). But I had no idea that Taoism and even Confucianism also held doctrines. As near as I can determine (not being an expert in East Asian cultures or religions), the Taoist and Buddhist “messiahs” were more of a religious nature, while the Confucian sect espousing such looked for a “sage-emperor” who would usher in a political golden age. These beliefs became especially prominent during, and after, the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD).

Thus, the Taiping Uprising (1850-1864), which killed at least 20 million Chinese, might not be solely attributable to Christianity, as it’s usually presented. It very possibly had deeper roots in Chinese society, which Hong Xiuquan bloodily tapped into. And the Communist rulers of modern China might not just fear the “foreign religions” of Christianity or Islam; they probably know full well their own civilization’s millennia-long history of having to deal with intrinsic apocalyptic insurrections.

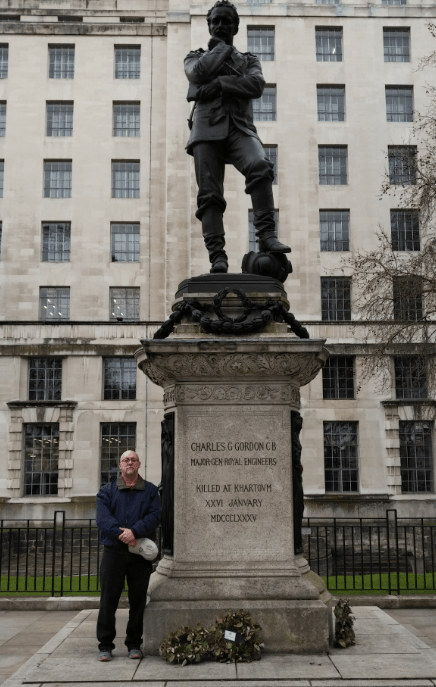

There was one man who dealt with both Chinese and Islamic messianic movements. Major-General Charles Gordon, who died defending Khartoum from the forces of the Sudanese Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, had earlier in his career helped the Qing rulers put down the apocalyptic Taiping cultists.

Yours truly honoring General Gordon, London, 2019.